By Dr Julia King, Lead Curator, Incunabula and 16th Century Books at the British Library (formerly Rare Books Librarian at Lambeth Palace Library)

Two recent acquisitions1, made possible by generous grants from the Friends of Lambeth Palace Library, the Trustees of Lambeth Palace Library, and the Friends of the Nations’ Libraries, highlight the ways in which the Church and the Crown sat on shifting sands during the tumultuous 1520s and 1530s. The first is a printed edition of Bishop (later Saint) John Fisher’s sermon against Lutheranism, given at St. Paul’s Cathedral on 11 February 1526. The second, printed in 1531 or 1532, is a work most likely by Henry VIII himself, known as A Glasse of the Truthe, wherein a lawyer and a priest debate the thorny matter of the King’s divorce and, more broadly, papal supremacy, landing on the side of the King.

The strict Roman Catholic orthodoxy of Fisher’s 1526 sermon contrasts with the radical notions of an independent Church seen just five years later in the Glasse of Truthe. Henry VIII’s title ‘Defender of the Faith’ was bestowed upon him by the Pope as a reward for his 1521 book Assertio Septem Sacramentorum, which defended the seven sacraments and spoke against Martin Luther and his views. Fisher’s sermon falls within this tradition of Henrician orthodoxy: he writes, ‘My duty is to endever me after my poure / to resist these heretickes / the which seasse nat to subvert the churche of Christe’. Fisher’s rhetoric is militant, and, according to the later sixteenth-century writer John Foxe, the sermon was itself accompanied by the burning of ‘great basketfuls’ of books.

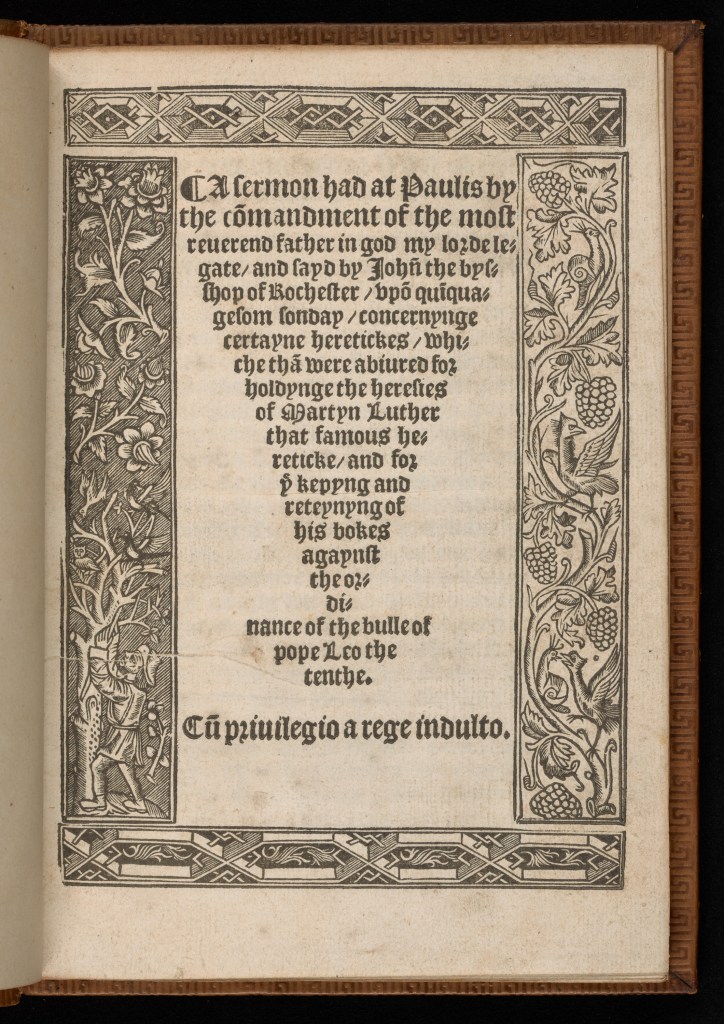

Fisher’s sermon accompanied the public penance of Robert Barnes, a Cambridge academic turned Lutheran theologian. Barnes had preached a sermon on Christmas Eve, 1525, based on Luther’s own sermon on the epistle for the day, and featured not only a diatribe against clerical excess, but also criticized Cardinal Wolsey and his luxurious style of living. His penance was held in a lavish ceremony where Wolsey and thirty-six other bishops and abbots watched him process around St. Paul’s Cathedral, carrying a bundle of wooden sticks, while Fisher read his sermon. This sermon was printed by the King’s printer, Thomas Berthelet, and is extremely rare, existing in only 6 variant copies; Lambeth’s variant is recorded only here and at the Bodleian Library.

Barnes later faked his own death and escaped to the continent, where he met and befriended Luther himself. He returned to England after the break with Rome and helped to negotiate Henry VIII’s marriage to Anne of Cleves. However, by 1539, Henry VIII had broken with Rome but had also renounced Lutheranism. Barnes, living openly as a Lutheran, was executed in 1540. Ironically, John Fisher, who had preached so vehemently against Barnes in 1526, had himself been executed for denying the King’s supremacy as Head of the Church of England in 1535. Though the cause of each of their executions was their respective Roman Catholic and Lutheran beliefs, the formal charge against them was the same: treason.

The religious instability that doomed Barnes and Fisher was precipitated not only by the rise of Protestantism on the continent, but also by Henry VIII’s marital troubles. At the same time that Fisher was delivering his sermon, Henry VIII was becoming increasingly serious in his courtship of Anne Boleyn, and by 1527 had informed Catherine of Aragon that he wished to seek an annulment. In 1531, the earliest year that A Glasse of the Truthe could have been published, negotiations with Rome had irrevocably broken down. It was in this year that, after pressuring the Convocations of Canterbury and York, Henry VIII became Supreme Head of the English Church.

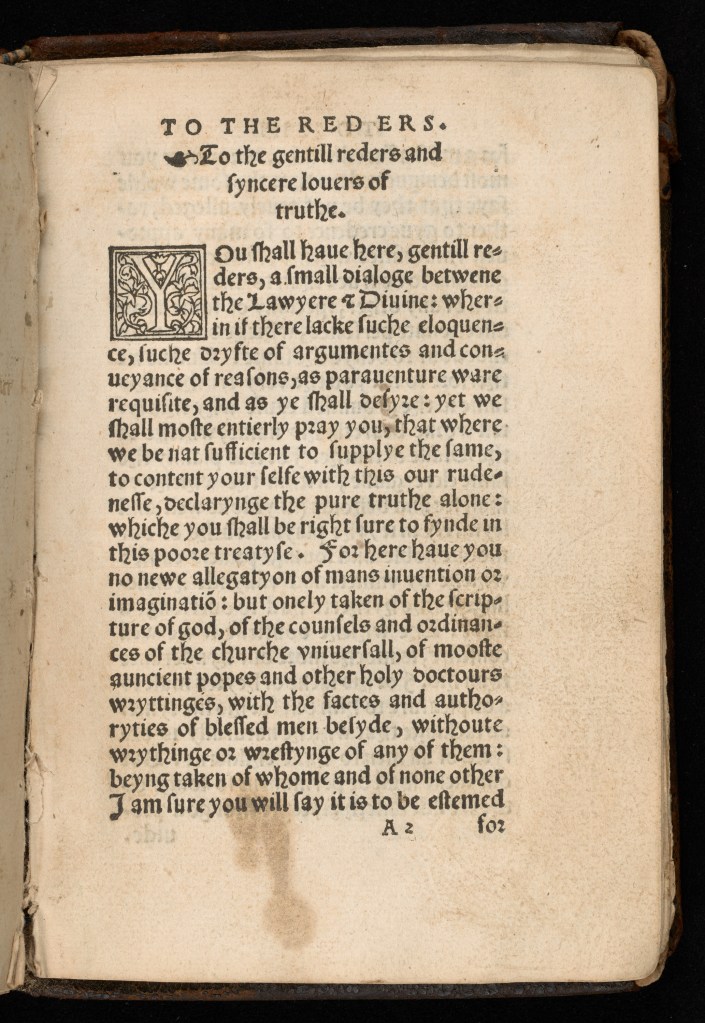

The next step for Henry and his ministers was to change the hearts and minds of both theologians and laymen alike. The second new acquisition, a book containing both Henry VIII’s own work known as A Glasse of the Truthe, and also Cranmer’s translation of The determinations of the moste famous and mooste excellent Universities of Italy and Fraunce, is an extremely rare example of Henrician propaganda dating from this period between Henry becoming Supreme Head of the Church and his eventual 1533 marriage to Anne Boleyn. Like Fisher’s sermon, both were printed by Thomas Berthelet, the King’s printer, showing the shift of royal priorities from 1526 to 1531.

The tone of A Glasse of the Truthe is different to the theological prose of The determinations. It takes the form of a fictional debate between a divine and a lawyer, and the tone is more colloquial. For example, the figure of the lawyer, discussing Catherine of Aragon’s earlier marriage to Henry’s brother Arthur, says that ‘truly no man is to be belevid in his owne matter. And (as one sayd) may a man bileve that a mayden accompanieng with a Yonge man of lust shal returne as she was a mayden?’ By the end, the divine is convinced of the King’s supremacy, saying, ‘These things be so pithily spoken and set for the that the can not be avoyded. Wherfore sins the truthe favoreth our princis cause so moche: lette us his subiectes than not omyt nothe our zele ne yet our obedience to hym according to our allegiance.’

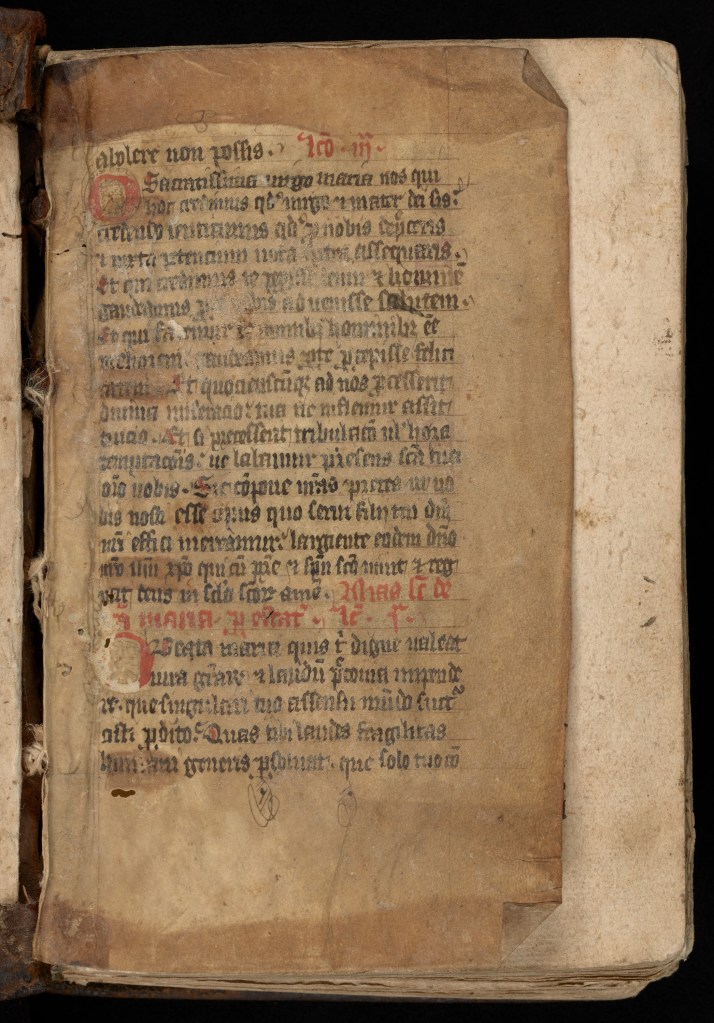

Lambeth already owns two copies of The determinations, an earlier account of the academic debates on the validity of the King’s marriage held between English delegates and the continental universities. However, because this new copy is bound with A Glasse of the Truthe (itself a much rarer work), both works share a typeface, and both are bound together in a sixteenth-century binding with two endleaves made of fifteenth-century English medieval manuscript waste (of possibly monastic origin), an interesting possibility appears. The two books may have been issued together or bound together, perhaps even by Berthelet, Cromwell, or another agent of the King, and distributed as a form of propaganda. We invite our readers to come and decide for themselves: was this a work of Henrician propaganda? Or was it put together by a reader collecting material related to current events?

These two books, both of the utmost rarity, are emblematic of the debates and controversies of the 1520s and 1530s. While Fisher’s sermon and the history surrounding it shows the tension between the Roman Catholic and Lutheran factions within the English Church, the Glasse shows just how quickly the landscape of religion in England had changed into something wholly its own – an independent Church of England.

- Fisher, John, A sermon had at Paulis by the co[m]mandment of the most reuerend father in God my lord legate : and sayd by John[n] the bysshop of Rochester, vpo[n] qui[n]quagesom Sonday, concernynge certayne heretickes,… [London, 1527?], H5133.F58S3 1527.

Acquired with the assistance of the Trustees of Lambeth Palace Library, 2025.

Henry VIII, A glasse of the truthe. [London, 1531-2?],

H2250.F6D3 1531 02.

Acquired with the assistance of the Friends of Lambeth Palace Library, the Trustees of Lambeth Palace Library, and the Friends of the Nations’ Libraries, 2025.

↩︎