By Ted Simonds, Sion Project Cataloguer and David Thomas, Assistant Librarian

Pindar was a Greek lyric poet of the 5th century BC, who is known for his epinikion, or victory odes. These odes celebrated athletic victories at the four Panhellenic Games: Olympian, Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean. Pindar’s odes were first printed in Venice by Aldus Manutius in 1513, prior to this, Pindar’s poetry was preserved in manuscripts in a range of forms (from fragments and survivals in quotations, to scribal copies with lineages of transmission). While this isn’t the editio princeps, the 1515 Pindar is a first separate edition, and the first to include the scholia (explanatory commentary).

The printer responsible for this work was the Cretan-born Zacharias Kalliergēs. He had spent time working in Venice (his native Crete was a Venetian colony at the time) as a printer of Byzantine and Greek works there, but moved to Rome at the invitation of Pope Leo X to teach at the short-lived Greek Gymnasium of Rome founded by Janus Laskari. Soon after arriving in Rome in 1514 Kalliergēs set up a Greek printing press in the villa of the renowned ‘tycoon’ Cardinal Agostino Chigi. Chigi has been called the richest man in Rome at this time, with anecdotes describing his decadence and records recounting some 20,000 people in his employ.

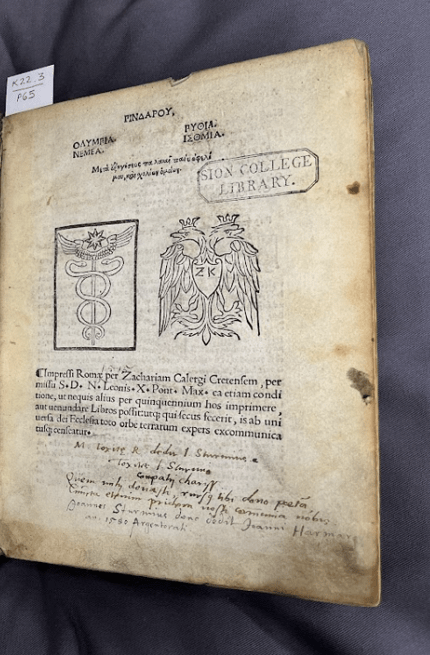

The 1515 edition of Pindar is Kalliergēs’s first work in Rome, and the first Greek book to be printed there. The cost of producing the work was met by money lent by Chigi to his chancellor Cornelius Benignus. It is Benignus’s device of the caduceus (winged staff of Hermes) that is printed alongside Kalliergēs’ printer’s device (double-headed eagle) on the title page. The loan required Benignus to sell his entire stock of Greek books in order to make the repayment.[1] The labour, expertise and expense of producing this important work of humanist literature is an enduring piece of literary work, and ‘may easily be designated the most important Pindar edition ever.’[2]

What makes this Sion College Library copy even more special is the illustrious list of former owners. The manuscript inscription (in Latin) on the title page introduces three of them: ‘M. Toxitae R. dedit I Sturmius a Toxites I Sturmi compatij chariss. Quem mihi donasti, rursg tibi dono preta[m], [Cuinta ethrium prichern nosti com[m]emia nobis?] Joannes Sturmius dono dedit Joanni Harmar an: 1580 Argentoriati’. To summarise, the book was given by Michael Toxites (1514/1515-1581) to Johannes Sturm (1507-1589), and from Sturm the book was given to John Harmar, (1555?-1613). Each man is worth learning a little more about.

The first named owner, Michael Toxites, was born in Sterzing in what is now the mainly German-speaking region of South Tyrol in northern Italy. He became a Latin teacher and poet and was recognised by Emperor Charles V in being named a poet laureate of the Holy Roman Empire at the Imperial diet at Speyer in 1544. Although still prestigious, this is not the same as the sole position in the UK today, indeed between 1355 and 1806, as many as 1500 people received the title. Toxites later studied medicine in Strasbourg, where he ran a laboratory and edited the works of the doctor and alchemist Paracelsus. It would have been in Strasbourg that the book was passed on to its next owner.

Johannes Sturm (Jean Sturm) was the leading educator of the Reformation and a devoted Classicist. He was born in the Duchy of Luxembourg and attended the Collegium Trilingue (College of Three languages, the three in question being Latin, Greek and Hebrew) in Leuven, where he was part owner of a press that printed Greek texts. Although Sturm embraced Protestant belief, his tolerant and mediating approach to confessional disagreements was rare for this period. While teaching at the University of Paris in the 1530s he tried to organise a meeting between the Reformers Bucer and Melanchthon and Francis I but this became impossible following the Affair of the Placards in 1534, when posters attacking the Mass appeared in several cities. With France becoming increasingly dangerous for Protestants, Sturm accepted an invitation to teach in Strasbourg. Once there, he consolidated the existing classical schools into a larger institution called the Schola Argentoratensis, which soon became the standard for German Gymnasiums (grammar schools). For forty-three years Sturm led the school whose humanist and interdisciplinary focus became renowned across Europe.

The first English owner of the book was John Harmar who was Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Oxford. Coincidentally he was the editor of the first Greek text printed in Oxford, an edition of John Chrysostom’s sermons (1586), which is also held at Lambeth. Harmar visited continental Europe before his appointment and this is where he would have met Sturm and received the book; ‘Argentoriati’ in the ownership inscription is a Latin name for Strasbourg. He also spent time in Geneva and befriended Theodore Beza where he ‘found him no lesse than a father unto me in curtesie & good will’.[3] Following his time in Oxford Harmar became headmaster (1588) and then Warden (1596) at Winchester College. Harmar is best known for being a member of the Second Oxford Company in the translation of the King James (Authorised) Bible. Not only did he translate the Gospels, Acts, and Revelation he is known to have served on the committee of reviewers who checked the complete text of the Bible.

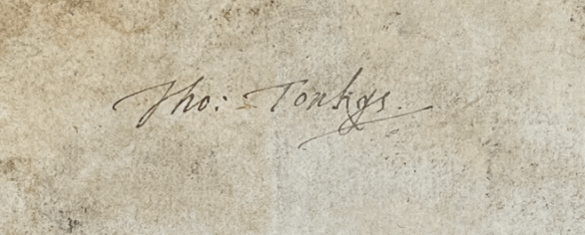

The final recorded owner, Thomas Tomkis (c. 1580-c. 1634), was an Elizabethan and Jacobean playwright, solicitor and book owner active at the end of the 16th century and early 17th century. Plays attributed to Tomkis include Lingua (1607), Albumuzar (1615) and Pathomachia (1630). Biographers know little of Tomkis’ life and berate his lack of ambition. After graduating from Trinity College, Cambridge, Tomkis is known to have given up his theatrical life and become a lawyer in Wolverhampton. It is unclear when and how Tomkis acquired the book, as the majority of Harmar’s Greek books were donated to his alma mater New College, Oxford.

A cache of books once belonging to Thomas Tomkis is emerging during the work to catalogue early printed books from the Sion College Library collection, held at Lambeth Palace Library since 1996. The majority of books with Tomkis’s manuscript inscription also have the bookplate of Durdans Library, the library of the Earls of Berkeley founded by Sir Robert Coke (1587-1653) at his house The Durdans, in Epsom, Surrey. More of Tomkis’s books have come into view following a project into the Durdans bequest in Summer 2023. Not all Tomkis books have the Durdans bookplate, calling into question the provenance of the books and also how thorough Sion College were with adding printed bookplates to donated books.

Many Tomkis books are 16th century and continental, with several having inscriptions indicating interesting provenances prior to them being owned by Tomkis. We can be thankful that Kalliergēs’ Pindar is one such volume.

[1] Giambattista D’Alessio, Review of The Kallierges Pindar: A Study in Renaissance Greek Scholarship and Printing In, Bryn Mawr Classical Review. 2017. Accessed September 2024. [https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2017/2017.07.27/]

[2] Fogelmark, Staffan, The Kallierges Pindar: A Study in Renaissance Greek Scholarship and Printing (Köln: Verlag Jürgen Dinter, 2015), p. 38.

[3] Botley, P. and Wilson, N.G., ‘Harmar, John’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 337