By Alison Day, Assistant Archivist

Workhouses were some of the earliest forms of health and social care for the population. Gaining a grim, but not undeserved reputation for brutality and dirtiness through writers such as Dickens and Orwell, their original intention was to provide support to the poorest members of society. Over a long and complicated history, workhouses were places of education, medical care and pastoral care, but also places of great suffering. In the first half of the twentieth century the multifaceted role of workhouses was split across the National Health Service, local education authorities and local councils.

Early poor relief was to some extent dependent on monasteries providing “dole” to members of the local community who were unable to support themselves. In 1388 Richard II passed the Statute of Cambridge which limited the movement of peasants and established rules that local areas had to take care of the poor in their own vicinity rather than forcing them to migrate elsewhere. This was a response to labour shortages following the Black Death, with the intention of keeping labourers from travelling in search of different or better paid work.

Following the Act For the Relief of the Poor in 1601, workhouses were built and overseen by the local parish, which meant that the link with the Church was ingrained. They became a government-provided service under the Poor Law Unions which were established in 1834. Poor Law unions were groups of parishes with a Board of Guardians who administered the workhouses. The majority of records from Poor Law Unions can now be found in local county record offices and are searchable through the National Archives Discovery Catalogue.[1]

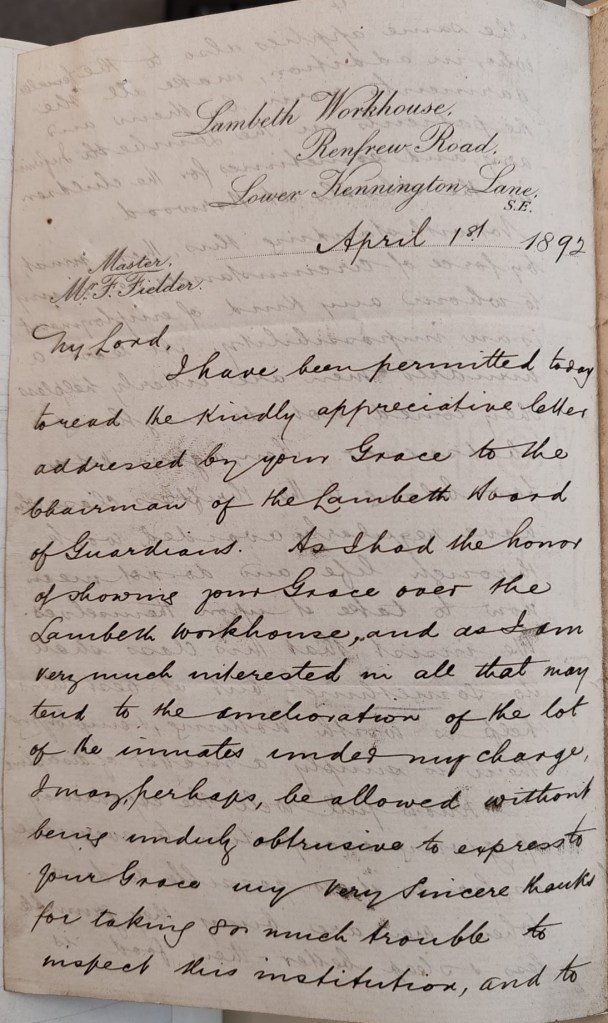

The local workhouse was part of the Archbishop’s visitation, where a questionnaire would be sent to all the clergy in a diocese every three or four years. The letter above was written in 1892, from the Master of Lambeth workhouse, Frederick Fielder, to Archbishop Edward Benson. It appears that Benson was less than impressed at seeing inmates not working during his visit and Fielder explains that the workday had finished when the Archbishop visited and that the larger ward was being cleaned at the time[2]. Earlier in his career, Archbishop Benson was a schoolmaster where he gained a reputation for being a stickler for the rules, and it appears that this was still the case in his later years. Fielder clearly had strong feelings about his duty of care to help the inmates to improve themselves during their time at the workhouse and was less than impressed with government interventions. Lambeth Workhouse on Renfrew Street also gained fame as being a place where Charlie Chaplin spent time as a child. The building has now been repurposed as the Cinema Museum.[3]

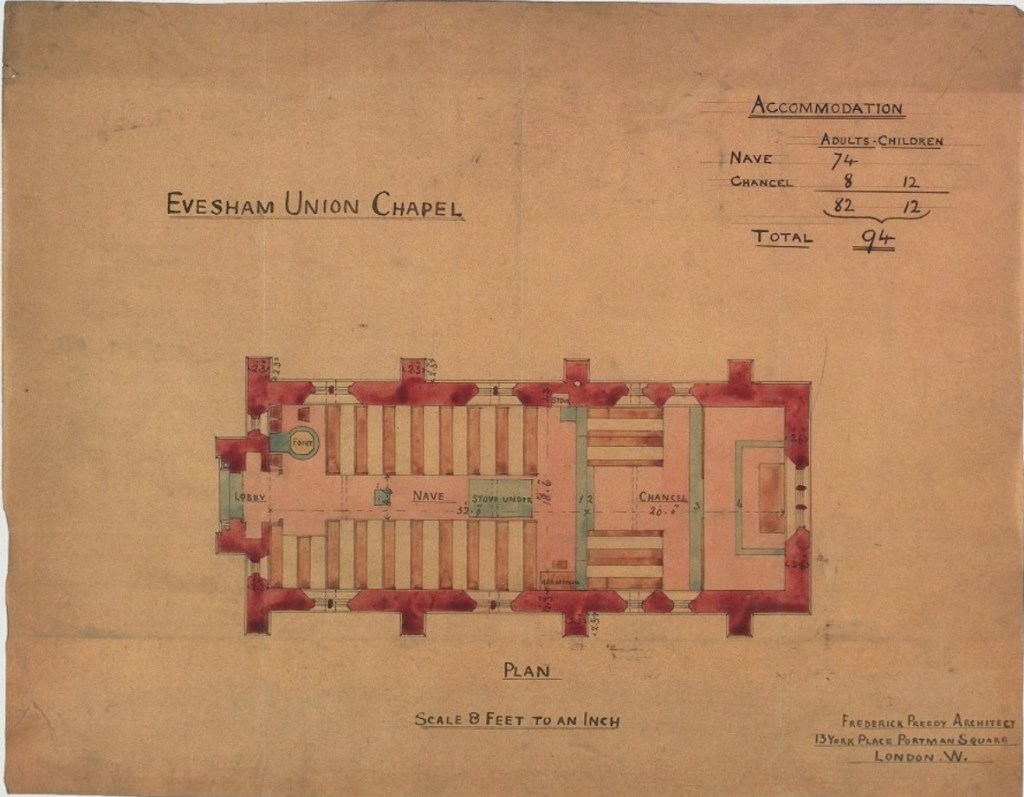

A Church of England chaplain was present in the majority of workhouses and was appointed and licenced by the Archbishop to look after spiritual matters within the workhouse. Many workhouses had a chapel on site, such as at Evesham, Worcestershire; its floor plan from the ICBS papers is shown above.[4]

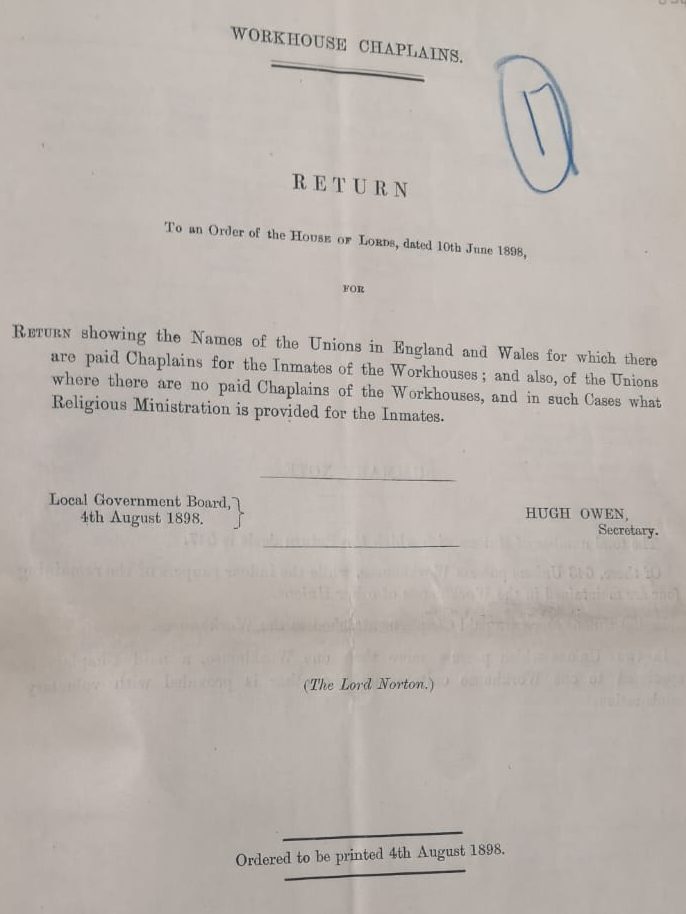

In the papers of Archbishop Frederick Temple from 1898 are the returns of a survey commissioned by the House of Lords to ascertain what religious provisions were available within the workhouses. Their findings showed that out of the 647 institutions surveyed, 459 employed paid chaplains, and where a union had more than one workhouse, one chaplain was appointed, and voluntary ministration occurred at the other.[5] This meant that another member of the clergy could visit, or the inmates would be permitted to leave the workhouse for a service. Historically this could have mixed results. In 1753 at the Croydon workhouse there was a complaint “that several of the Poor, let out of the House to hear divine service were frequently seen About Town begging and getting drunk.” It was subsequently ordered that anyone displaying this sort of behaviour would no longer be permitted to attend services outside.[6]

The Local Government Act of 1929 abolished workhouses and Boards of Guardians. The outbreak of World War I meant that workhouse staff often joined the military which caused staffing shortages in the workhouses. As casualties returned from the front, some workhouses were repurposed as hospitals, or used for refugee housing. Westminster Union Workhouse (formerly St James’ Westminster) in Poland Street was closed in 1913 and then used to house Jewish refugees from Russia.[7]

The Local Government Act transferred responsibility back to the community for care for the poor at a local level. However some workhouses did survive as ‘Public Assistance Institutions’, with nearly 100,000 people living in these former workhouses in 1939. The National Assistance Act 1948 finally ended the remaining Poor Law. With the introduction of the National Health Service in 1948 health and social care services were transformed.

[1] https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/

[2] Benson 129 ff. 11-16

[3] http://www.cinemamuseum.org.uk/

[4] ICBS 8478

[5] F. Temple 17 ff. 354-78