A new catalogue of the exhibits in the Court of Arches (Arches Ff) has been completed by Dr. Richard Palmer and is accessible as part of the Library’s online catalogue of manuscripts and archives.

The exhibits were presented in court as evidence and remained in its registry, forgotten or unclaimed by their owners but now representing a treasure trove for the history of the church, for local history, genealogy and many other subjects. Amongst them are accounts of churchwardens and overseers of the poor, rate books, estate records, surveys, leases, wills, probate inventories, account books, faculties for pews and alterations to church buildings, marriage certificates and settlements, records of lower courts and a wide variety of other documents.

Most of these records would not normally be sought at Lambeth but survive here by the accident of their presentation in court. They relate to parishes throughout the Archbishop’s Province of Canterbury, sometimes filling gaps in archives held locally. Examples include court books of the Archdeaconry of Middlesex, clergy books used in visitations of the Archdeaconry of Cornwall, and assignation books of the Consistory Court of Bath and Wells and the Archdeaconry Court of Suffolk.

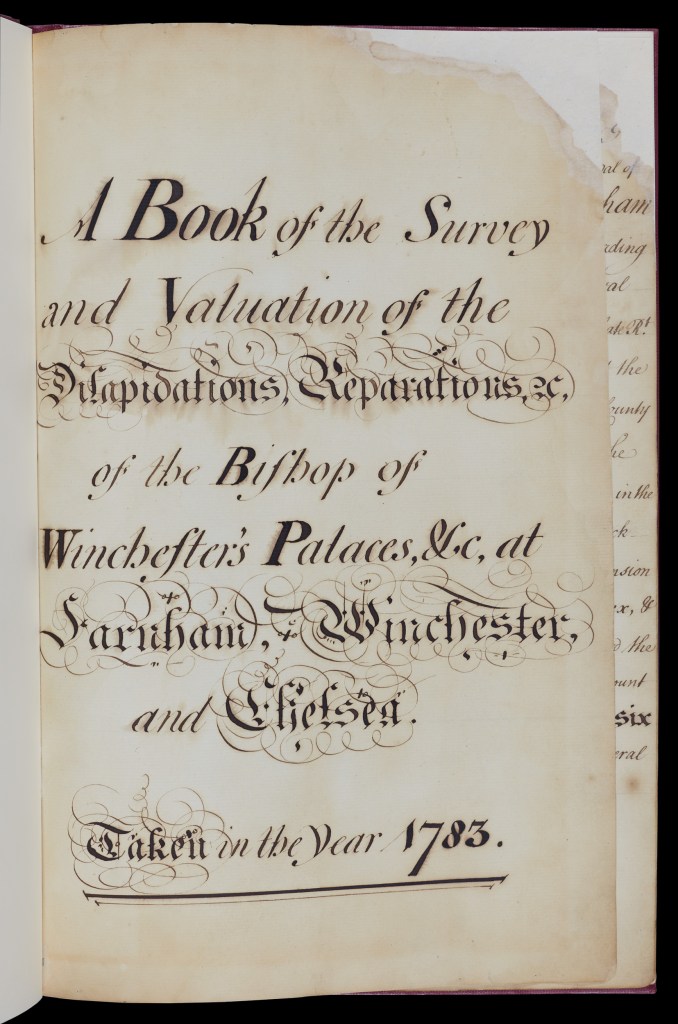

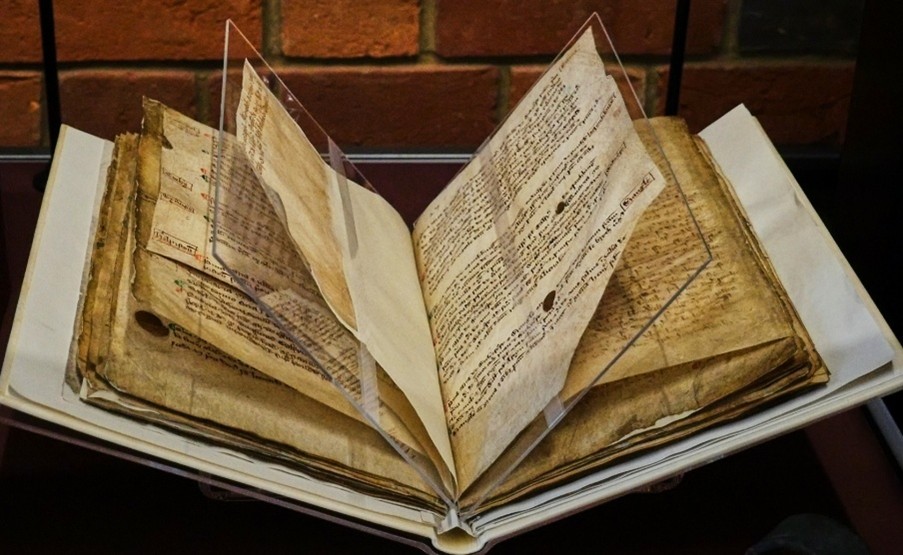

Time and again the exhibits are surprising. Who would expect to find the account books of a Lichfield mercer, the building contract for a house designed by the architect Kenton Couse, estate records relating to parishes as remote as Llanddewi Brefi and Bettws Bledrws, Cardiganshire, a description of the battle of Malaga in 1704 (in a series of letters from a navy captain to his lover), building leases tracing the development of Soho and Seven Dials, depositions concerning the marriage of the rake Beau Fielding to Barbara Palmer (née Villiers), Duchess of Cleveland, a note of the purchase of a chimney piece by the sculptor and stonemason John Hinchcliffe, surveys of dilapidations of the palaces of the Bishop of Winchester (pictured above), the medieval cartulary of Fineshade Abbey, Northamptonshire (pictured below), or the foundation charter of a college for priests in Ruthin in 1310?

The churchwardens’ books and accounts relate to ten or more parishes in England and Wales. Those for Ashburton, Devon, include receipts (for burials, pews, rents for church land), disbursements (for church fabric, bells and bell ringers, communion and visitation costs, apprenticeships, the repair of bridges, the poor, vagrants, almshouses, the courthouse, gaol, stocks and cage), and also expenditure during the Civil War for arms and training, maimed soldiers, a hospital, and ‘going to Exeter to fetch ammunition for Sir Henry Caryes regiment’. Together with rate books and accounts of the overseers of the poor, such records are a goldmine for local and family historians, alongside exhibits such as registers of burials at North Mymms, Hertfordshire, 1591-1627, and of baptisms, marriages and burials at Dorney, Buckinghamshire, 1696-1726.

Strays from records of other courts which used the same premises as the Court of Arches are also found. Many relate to the Prerogative Court of Canterbury and others to the High Court of Admiralty. Amongst the surprises in the archive are logs of French ships trading with India and China and notes on navigation, probably from vessels captured during the Seven Years’ war.

Most exhibits date from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but later documents include plans of the churches at Kibworth Beauchamp, Leicestershire, and Chesterfield, Derbyshire. Relating to controversies over ritual in the nineteenth century are photographs of a reredos at Denbigh, drawings of bosses in Exeter Cathedral, controversial printed books and, remarkably, the original presentation to the vicarage of Brampford Speke of George Gorham, which sparked one of the most heated arguments of the period.

The catalogue can be searched online at: CalmView: Home Page (lambethpalacelibrary.org.uk)