By Matthew Harper, Archives Assistant

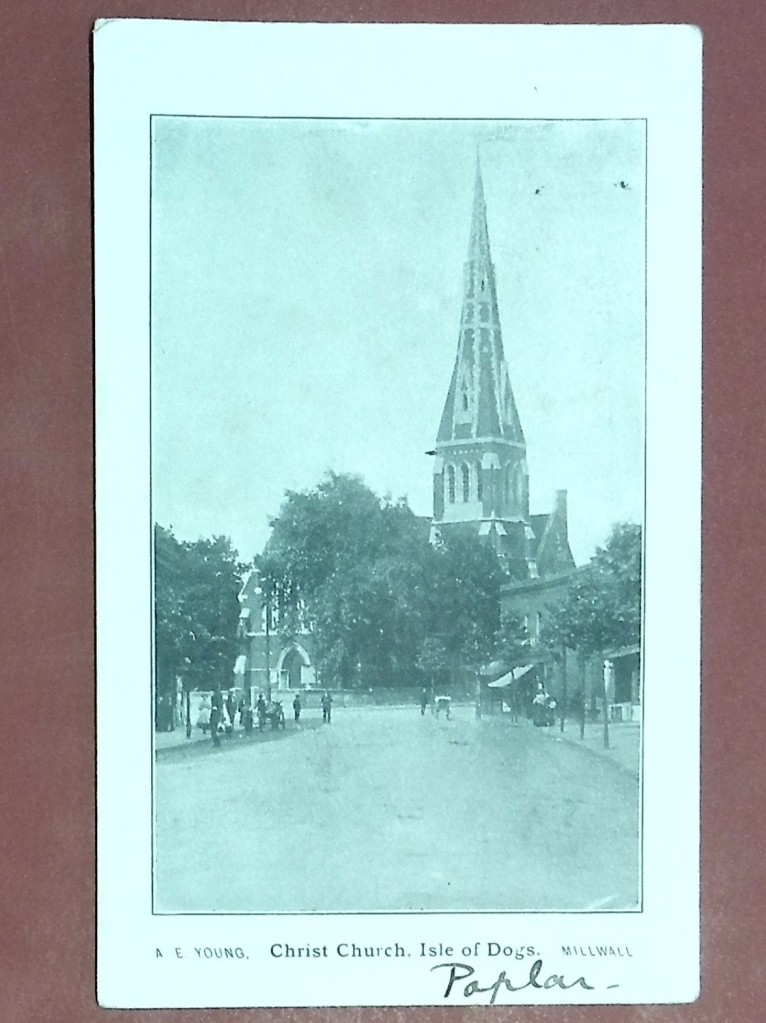

The Isle of Dogs is an island a few miles east of the City of London.[1] Prior to the building of the docks, there was not a great deal of activity on the Island, and most outsiders would have had little interaction with it, except for travelling past, or taking the ferry across the river to Greenwich or Deptford.[2] Samuel Pepys mentioned the Isle of Dogs in his diary on the 31st of July 1665. He took the ferry across the Thames to the ‘Unlucky Isle of Doggs’ where he was forced to spend ‘two, if not three hours to [his] great discontent’.[3]

This changed at the beginning of the 19th century, with the opening of the West India and East India Docks. In the 1840s the engineer William Cubitt (1791-1863), later Lord Mayor of London (not to be confused with the engineer of the same name who built the Crystal Palace) began building houses and businesses on the eastern side of the Island, in what is now known as Cubitt Town, to accommodate the influx of workers in the docks and the associated industries that grew around them.[4] The population of the Island increased from approximately 200 in 1800 to 14,000 by 1860.[5]

Cubitt, who has been described as a devout man, decided that the new population needed a church. Prior to the building of Christ Church, the closest Anglican church north of the river was All Saints, Poplar which was two or three miles by foot.[6] Initially, land and a donation towards the construction of a church in Cubitt Town was offered by Cubitt to Charles Blomfield, Bishop of London in 1847, but this offer was not acted upon. It was not uncommon for offers like this to be made in London at this time, and Bishop Blomfield usually encouraged the construction of churches through private donations of land and funds.[7]

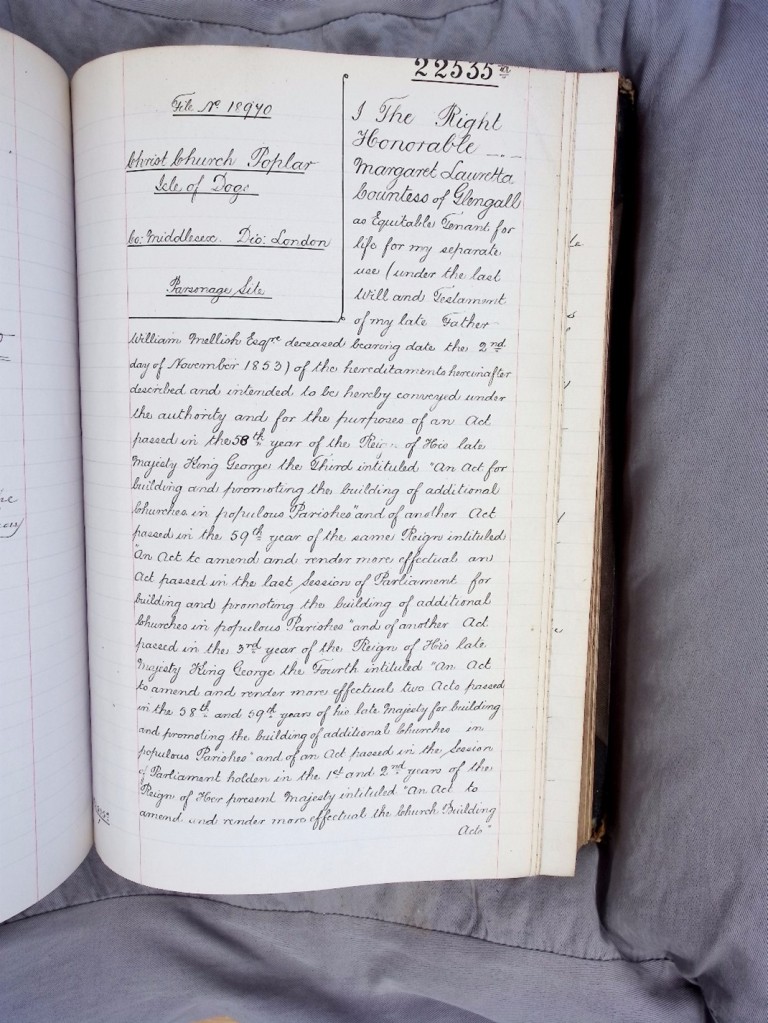

As a result of his offer not being accepted, William Cubitt began to finance the construction of the church out of his own pocket in 1852.[8] The church was designed by Frederick Johnstone, and was completed by 1854.[9] It was said, shortly after construction was completed, that some stone from the old London Bridge (demolished in 1831) was used in the building of Christ Church.[10] Copy deed number 22,535A, held at Lambeth Palace Library and dating from 1859, shows that William Cubitt and the Countess of Glengall, who owned the freehold to the land, had donated the site of the church and vicarage.[11]

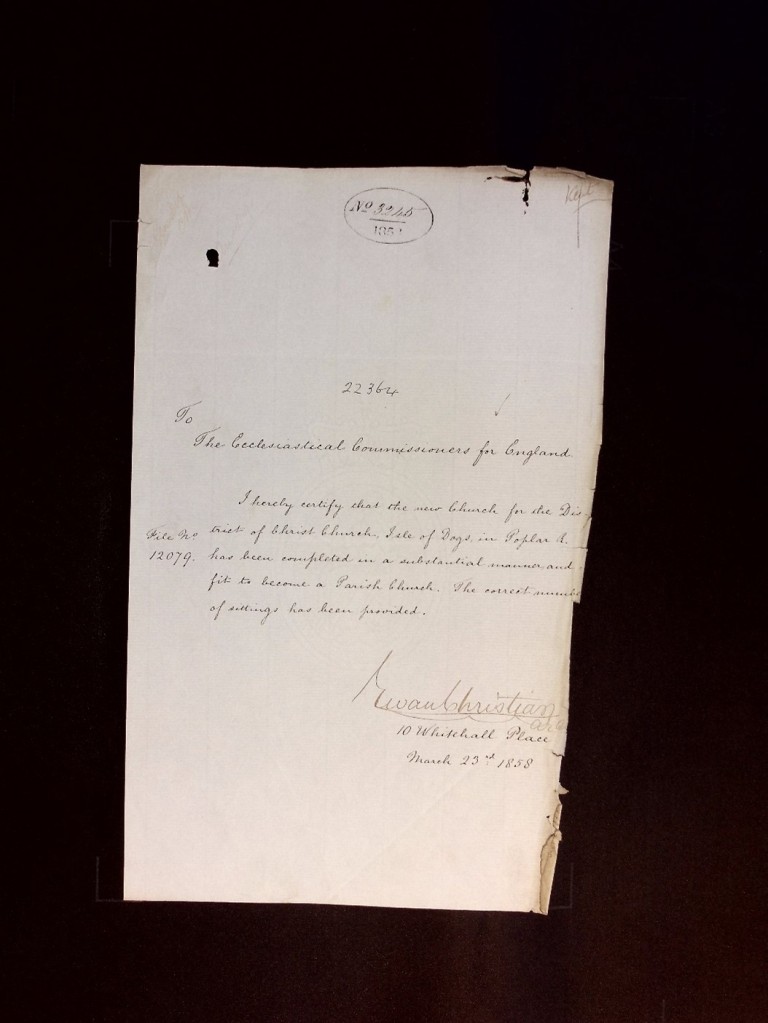

There was, however, a delay between the completion of the church and its consecration, with the church being completed in 1854, but not consecrated until 1857. It has been suggested that this was caused either by administrative delays caused by the change in bishop or the unfinished state of the church.[12] The ill health of Blomfield prior to his retirement in 1856 lends weight to the suggestion that the consecration was postponed due to administrative problems, although this is speculation, and I have not come across material that definitively settles this debate.[13] The collections at Lambeth Palace Library might support this, as although services had already began in the church by January 1857, it was not until March 1858 that the Ecclesiastical Commissioners received a letter of confirmation from Ewan Christian that the building had been ‘completed in a substantial manner’ and was fit to become a Parish Church, in which he makes no mention of there having been problems with the building previously.[14] Christian was the architect to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners and the fact that he did not inspect the church for a total of four years, and over a year after services began suggests that this was the reason for the delay.[15]

Since then, the vestry of the church has been enlarged and general repairs were undertaken in the early years of the 20th century.[16] Christ Church suffered some bomb damage during the Second World War, like much of the Docklands, although it was not hit directly and was later repaired.[17] It remains, to this day, a central part of life on the Isle of Dogs and is one of the last buildings built by William Cubitt still standing in Cubitt Town.[18] The collections at Lambeth Palace Library contain a significant amount of material relating to churches and land owned, or previously owned, by the Church Commissioners and their predecessors. Similar research to this blog post could be done using the Copy Deeds series (ECE/6/3), the Ecclesiastical Commissioners files (ECE/7/1), as well as the collection of deeds and Church Buildings department survey files.

Bibliography of Secondary Sources and Further Reading

Hostettler, Eve, A Brief History of the Isle of Dogs Volume 1 1066-1918 (London: Island History Trust, 2000).

Hostettler, Eve, The Anglican Church on the Isle of Dogs (London: Island History Trust, 2004).

Lemmerman, Mick, “Historic Isle of Dogs Churches”, Isle of Dogs – Past Life, Past Lives, 13th November 2016[Accessed 5th February 2024], https://islandhistory.wordpress.com/2016/11/13/historic-isle-of-dogs-churches/

Mackeson, Charles, A Guide to the Churches of London and its suburbs for 1867 (London: Metzler, 1867).

Matthew, H. C. G. and Harrison, Brian, (eds.), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Volume 11, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Pepys, Samuel, The Diary of Samuel Pepys Volume VI 1665,. Robert Latham and William Matthew (eds.) (London: G Bell and Sons, 1972).

Pevsner, Nikolaus, Cherry, Bridget and O’Brien, Charles, London 5 East (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2005).

Porter, Steven (ed.), Survey of London Volume XLIV: Poplar, Blackwall and the Isle of Dogs (London: Athlone Press, 1994).

[1] Some sources consider the Isle of Dogs to be a peninsula because it is surrounded by the Thames on three sides and they do not consider the docks that bound the Island to the north to be bodies of water.

[2] Eve Hostettler, A Brief History of the Isle of Dogs Volume 1 1066-1918 (London: Island History Trust, 2000), pp.10-11.

Eve Hostettler, The Anglican Church on the Isle of Dogs (London: Island History Trust, 2004), p.7.

[3] Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys Volume VI 1665,. Robert Latham and William Matthew (eds.) (London: G Bell and Sons, 1972),p.175.

[4] Steven Porter (ed.), Survey of London Volume XLIV: Poplar, Blackwall and the Isle of Dogs (London: Athlone Press, 1994), p.499.

[5] Hostettler, History of the Isle of Dogs Volume 1, p.22.

[6] Hostettler, The Anglican Church on the Isle of Dogs, p.12.

[7] Malcolm Johnson, Bustling Intermeddler? The Life and Work of Charles James Blomfield (Leominster: Gracewing, 2001), pp.106-109

[8] Survey of London, p.507

[9] Nikolaus Pevsner, Bridget Cherry and Charles O’Brien, London 5 East (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2005), p.701.

[10] Charles Mackeson, A Guide to the Churches of London and its suburbs for 1867 (London: Metzler, 1867), p.17.

[11] LPL ECE/6/3/313/CD22535A

[12] Hostettler, The Anglican Church on the Isle of Dogs, p.14.

Mick Lemmerman, “Historic Isle of Dogs Churches”, Isle of Dogs – Past Life, Past Lives, 13th November 2016[Accessed 5th February 2024], https://islandhistory.wordpress.com/2016/11/13/historic-isle-of-dogs-churches/

[13] Johnson, Bustling Intermeddler?, p.147.

[14] LPL ECE/7/1/22364/1

[15] H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison (eds.), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Volume 11, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp.519-520

[16] Nikolaus Pevsner, Bridget Cherry and Charles O’Brien, London 5 East, p.701.

[17] Hostettler, The Anglican Church on the Isle of Dogs, p.37.

[18] Nikolaus Pevsner, Bridget Cherry and Charles O’Brien, London 5 East, pp.56-57.