How cathedrals changed in the 20th century as recorded in the CATH files, part 1

By Lizzie Hensman, Assistant Archivist

Almost 10 million people visited English cathedrals in 2019, and in spite of the pandemic there were 8.2 million visitors in 2022. These visits were for a variety of reasons. 37,000 people attended regular services each week and 800,000 attended services for special occasions in 2019. Cathedrals are important in people’s everyday experiences of God and provide destinations for pilgrimage. Yet they are also tourist attractions and sites of national memory. Their libraries hold important treasures and their windows, monuments and architecture are great works of art. Cathedrals need to find the right balance between these seemingly opposing uses. In order to continue to be relevant in an increasingly secular society, to preserve the treasures that they hold, and to fulfil their religious obligations, cathedrals have had to change over the last hundred years.

The papers of the central body responsible for advising Deans and Chapters on changes to their cathedrals show these tensions. This body is now called the Cathedrals Fabric Commission, but was established in 1949 as the Cathedrals Advisory Committee (CAC). The body became a General Synod Commission in 1981 and changed its name to Cathedrals Advisory Commission accordingly. The archive catalogue reference for these CAC records is CATH. Most of the records are correspondence files between the committee and the Deans or Chapters of cathedrals. These are arranged by cathedral with some topics being common to many cathedrals. This series of blog posts will highlight some of these threads and other ideas which can be found in this archive.

First lets get some vocabulary. [Feel free to skip this bit and just refer back when you find a term that you don’t recognise]. Cathedrals and great churches tend to follow the same arrangement. They are cross shaped with an extravagant entrance (West Front) at one end, which leads onto the Nave which can be filled with seats for big services or cleared to be used for other functions. Walking forwards down the nave there could be side chapels on either side, these can be used for smaller services. Around halfway into the cathedral are the Transepts, these form the arms of the cross. As you walk through the Crossing (where the transepts meet the nave) you often have to go up some steps or through an opening in a screen. This separates the Nave and the Quire (or Choir). This will have luxurious wood panelled pews and is where dignitaries and the choristers sit in whole cathedral services, or can be used as a chapel on smaller occasions. Continuing East you will reach the High Altar. This is the holiest and often most elaborately decorated part of the cathedral. An intricate Reredos often rises up behind the altar standing in relief in front of a dramatic East Window. Many cathedrals will also have a Lady Chapel, this is a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary and (as in the example above of Hereford) is often behind the high altar. Outside the main cross shape of the cathedral you can also have Cloisters. These tend to run along one side of the Nave and transept to form a square and off these you will find an, often circular, Chapter House. The Chapter are the people who, with the Dean, run the cathedral and assist the Bishop in managing the diocese.

So what changes were Deans and Chapters making to their cathedrals?

Much like with clothing, architecture has fashions. Victorian gothic designs were no longer popular and a movement to restore cathedrals to their original medieval designs was taking hold. To many Deans these recent additions weren’t old enough to be considered history worth saving and certainly weren’t original so they had to go. Cathedrals across the country were ripping out their reredoses and screens by Victorian cathedral architects such as George Gilbert Scott. But what should be done with them? They are important artefacts in the history of cathedral architecture and impressive works of art. However, elaborate metal screens, big enough to separate the quire from the nave don’t have many other uses. They could be offered to another cathedral but as the fashion was for removing them this wouldn’t work for many. The Winchester screen was sold for scrap because the Dean was so determined to get rid of it. Others found their way to museums. The Skidmore Screen, from Hereford Cathedral, was originally given to a gallery in Coventry in 1967 but it would have cost so much to restore it that it was simply left in storage. It is now on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum after lottery funding allowed for its full restoration.

New church traditions suggested screens were unnecessary. Keeping them would limit the ability of the cathedral to stay relevant. They prevented someone who has walked in the west end of the nave from seeing the altar and separated the clergy from the people. New cathedrals were being built, in Guildford and Coventry where a big open nave lead seamlessly through to the East End, inviting the visitor though. This was justified liturgically by the claim that the original English great churches were arranged as such.

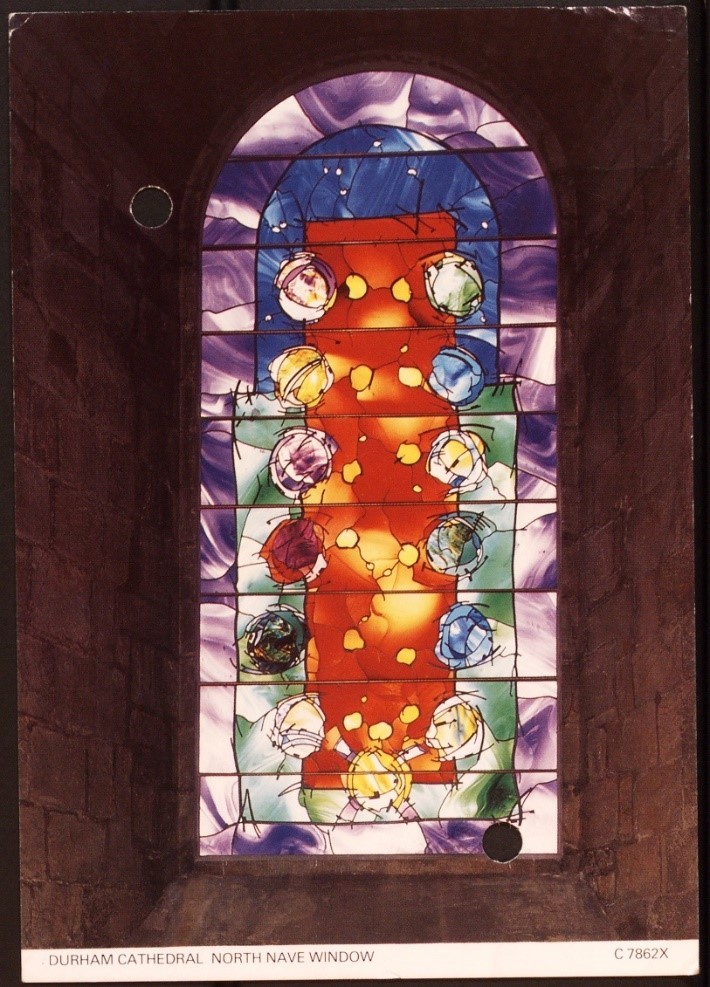

Removing these features also created space for new artworks to be commissioned. This allowed modern artists the honour of designing something to be displayed in a building of national importance and strengthened links with the community the buildings served. Designs for candle sticks, altar frontals, windows, statues, reredoses, nativities and fonts can be found throughout the series. For example the Daily Bread window designed by Mark Angus was dedicated in Durham Cathedral in 1984, Ursula Benker-Schirmer’s tapestry in the Shrine to St Richard at Chichester, and new altar frontals for the Lady Chapel at Rochester Cathedral.

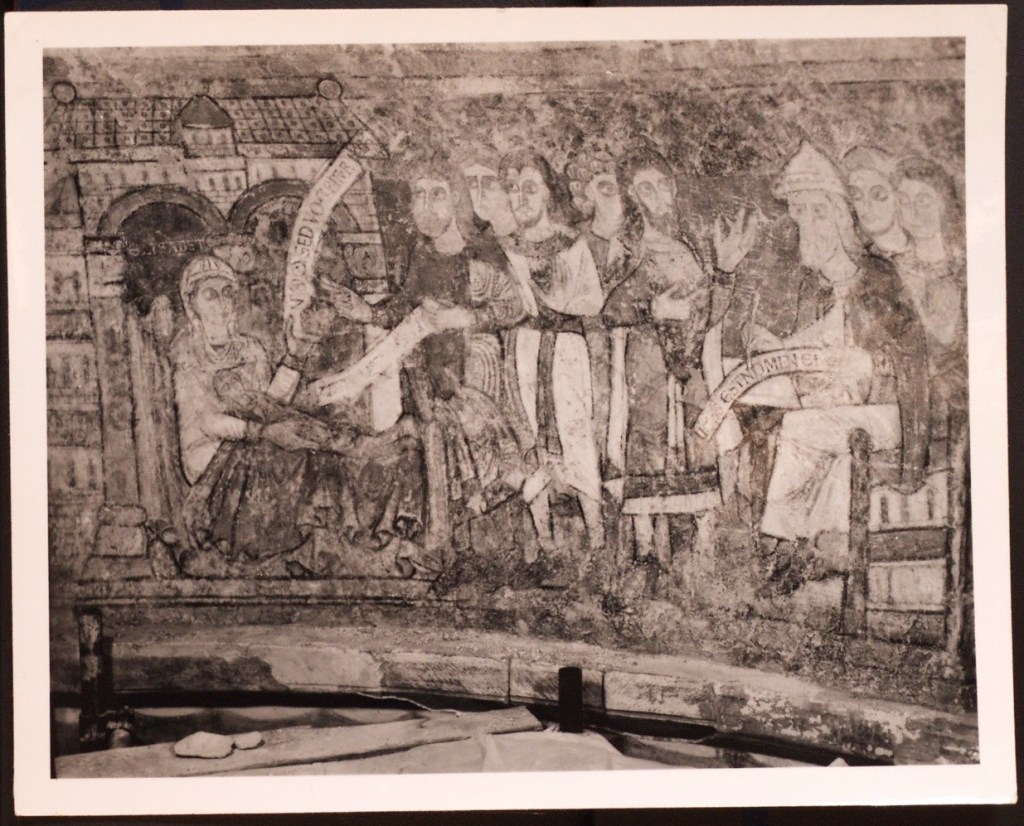

Some ancient features of cathedrals were seen as worth keeping, particularly wall paintings. Medieval cathedrals would have been seething with colour. The walls would have been painted with biblical scenes. Evidence of this can still be seen on some walls of cathedrals today but without careful restoration work it would have been lost. Over the 20th century various approaches were taken to the preservation or restoration of these murals. In Canterbury’s Jesus Chapel the wall paintings were restored to their original condition. This is striking and brings life to the cathedral, treating it as a current space. However the decision drew criticism as it involved painting over the original work, meaning future scholars could not examine it.

Many cathedrals employed the help of Mrs Eve Baker, her husband Professor Robert Baker and her team. They painstakingly restored wall paintings from Durham to Winchester and Hereford to Norwich. Her work was generally considered to be beyond compare but her estimates were often optimistic. Many files contain Deans despairing at the unexpected expense. This work was often paid for by grants from the Pilgrim’s Trust which meant repeat applications were often required to compete the restoration of wall paintings in a single chapel. Her work sometimes even discovered new wall paintings hiding under more recent ones.

Treasuries and museums were also created to allow for the display of cathedral treasures and the education of visitors. This provided a home for communion plate from churches in their diocese which would otherwise be locked in vaults, enriching the visitor experience by allowing the treasures held by local churches to be viewed by the public. Many of these were created using grants from The Goldsmiths’ Company. Correspondence shows them approaching Deans directly or the CAC suggesting them as sources of funding to cathedral representatives.

All of these changes meant that the architecture, history and objects held by cathedrals were made more accessible. This encouraged visitors, confirming the idea that cathedrals were tourist attractions as well as places of worship. This will be elaborated on in the next instalment.