By Hugo Craft-Stanley, Archives Assistant

Sometimes, walking down the ramp at Waterloo East station, you can catch glimpses of the 1930s housing estate below.

There is a rich seam of social history behind these ordinary-looking blocks of flats. They were built by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners as a slum clearance project in 1938. The estate replaced Ethelm Street, a terrace troubled by overcrowding and poor living conditions. An estimated one thousand people lived on this single street, a quarter of whom were children, in 72 two-storey houses.1 It was not uncommon to find entire families, with four or five children, living in a single room. There were boarding houses letting beds to lodgers by the night, with as many as three beds to a room.

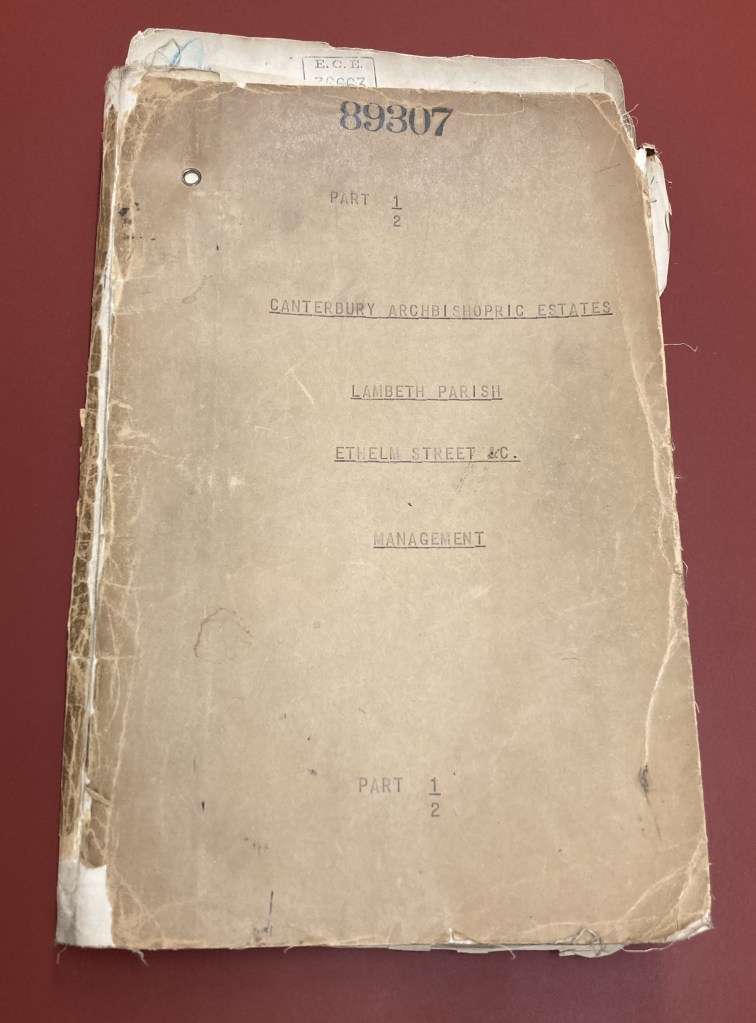

Since last September I have been working on a project to catalogue files documenting the history of Ethelm Street and other working class housing estates formerly owned by the Church Commissioners. These files, from the archives of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, are a remarkable resource for studying the social history and urban development of this part of London from the nineteenth century up to the present.

In a file from the Commissioners’ archives, I came across a series of photographs of Ethelm Street in the 1920s. They provide a fascinating window onto this vanished place.

This photograph was taken on Ethelm Street 102 years ago, in July 1922. We see a group of people standing in the street, with the terrace of two-storey houses stretching away into the distance. The children are half-smiling. One boy’s trousers are ripped at the knees; two of the children are barefoot.

In this second photo, a group of women and children stand outside the Cathedral Playhouse, a former pub converted into a children’s club.

We hold these records because Ethelm Street was built on land owned by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, the body founded in 1836 that administered the Church of England’s property assets. It still exists today as the Church Commissioners, formed in 1948 as a merger of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners and Queen Anne’s Bounty, which was a fund for poor clergy established in 1704.

During the cataloguing project, I developed a growing curiosity about the history of Ethelm Street. In particular, I wanted to know how a place like this developed on Church-owned land. Whilst the files I was cataloguing focused on efforts to improve conditions on Ethelm Street in the 1920s and 1930s, concluding in a slum clearance project that saw the street demolished and rebuilt, I wanted to illuminate the earlier history of this place. In this series of blog posts I will be exploring this history, drawing on the Ecclesiastical Commissioners’ extensive archives.

Ethelm Street had its beginnings in 1822, when a two-acre estate in Lambeth was leased to William Manfield by the Archbishop of Canterbury. The estate was later inherited by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. This was a building lease enabling Manfield to build houses on the site, lasting for a period of 99 years at an annual ground rent of £72: 5: 0 per year – roughly £7500 in today’s money. It is still in our collections today, with reference number TA/611/30, 31 (pictured below). At this time, the surrounding area was largely undeveloped. Waterloo Station, which is now just a few minutes’ walk away, would not be built for another 25 years. Waterloo Bridge had only opened in 1817, five years earlier. The area was only now being engulfed by the expanding city.

Soon after the lease was granted, William Manfield built a street of houses on the two-acre plot of land. It was named Ethelm Street. Manfield then sold his leasehold of the street to the Freeman family, who would collect rents on Ethelm Street’s houses for the next 99 years. This became a profitable investment: a 1910 report by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners notes that the “land comprised in the lease is now the site of some 90 or more houses, which of course provide substantial improved, or rack, rents.”2

It has proven difficult to find out how much these rents amounted to, but it would have been far more than the ground rent of £72: 5: 0 per year that the Freemans paid to the Commissioners. In 1923, after the Commissioners took over management, the total rental income for the estate was £2,880 per year, translating to roughly £147,173 per year in 2024.3 The Freeman family divided the net rents into shares, creating a trust to pay four out of a total of five shares to “various persons for life”.4

Overcrowding and poor living conditions were a serious problem on Ethelm Street, as in many working class areas in London during the Victorian period and beyond. The Ecclesiastical Commissioners’ files contain very little material that provides a sense of what life was like for tenants in such crowded conditions, instead focusing on the administration of the land itself. There is plenty of correspondence with the Freeman family and their solicitors, making it easier to use the archive to tell the story of the landlords than that of the tenants. However, I was able to find other sources that provide a sense of the atmosphere on Ethelm Street.

I discovered a 1897 newspaper article that describes the landlady of a boarding house on Ethelm Street letting “a bed in a three-bedded room” to a lodger, 18-year-old James Thompson. Boarding houses or lodging houses were common in working class London at the time, providing beds by the night in crowded rooms. Thompson was caught stealing a suit from another lodger and sentenced to six months’ hard labour in prison. He had only recently served three months’ imprisonment for a similar theft nearby, with around 30 cases of this kind against him across London. When the judge asked him what he had to say, he “burst into tears, and, speaking with a strong north-country accent, said, “I am guilty. I can’t get any work. I’m a stranger, and there is nothing for me to do but steal.”5

In the archives, I came across a striking account of living conditions in similar nineteenth-century properties owned by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners near Ethelm Street during the 1930s.

In 1933, a branch of the Church of England Men’s Society (C.E.M.S) invited Sir John Birchall, MP to inspect overcrowded properties on land owned by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners in Southwark, just a ten minute walk from Ethelm Street. Birchall was a member of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners and vice-president of the C.E.M.S. He had spoken at a conference earlier that year, where he stated that the Ecclesiastical Commissioners were not owners of slum property. After viewing the property, he wrote a letter to the First Church Estates Commissioner Sir George Middleton describing what he had seen:

It is unusual to find a description like this of the conditions in working class housing in the Ecclesiastical Commissioners’ files. The situation on Pepper Street was similar to that on Ethelm Street. At the end of a long lease these houses had returned into the possession of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners and plans were in motion to redevelop the area. However, people still had to live in poor conditions until this happened. There was a gap between the slow, bureaucratic process of change and the reality of life for the tenants.

One of the strange things about Ethelm Street is that whilst the Ecclesiastical Commissioners owned the land that the houses were built on, they were not responsible for the properties built there during the lease. As ground landlords they owned the land, but not what was built on it. I will continue to explore the complexities of this situation in my next blog post about Ethelm Street.

- Westminster Gazette, 3 November 1922, ECE/7/1/69406 ↩︎

- Letter of 18 July 1905 from the Freeman family’s solicitors, ECE/7/1/69406 ↩︎

- Bank of England inflation calculator ↩︎

- Letter of 18 July 1905 from the Freeman family’s solicitors, ECE/7/1/69406 ↩︎

- South London Press, 24 April 1897, accessed externally through British Newspaper Archive ↩︎