The papers of Archbishop Davidson (volume 346) document how planning was already in progress by 1918 on training of candidates from the armed forces for holy orders after the end of hostilities, including consideration of cases of disability.

In 1919 the Knutsford Ordination Test School opened. As recounted in R V H Burne’s Knutsford; the story of the Ordination Test School, 1914-40 (published in 1960), the institution was initially housed in the gaol at Knutsford, previously occupied by German prisoners and before that by conscientious objectors, but only until 1922, when it moved to other premises in Knutsford and from 1927 in Hawarden. It eventually closed during World War Two. Its aim was to provide education for demobilised servicemen so that they could obtain the qualifications required to study for ordination.

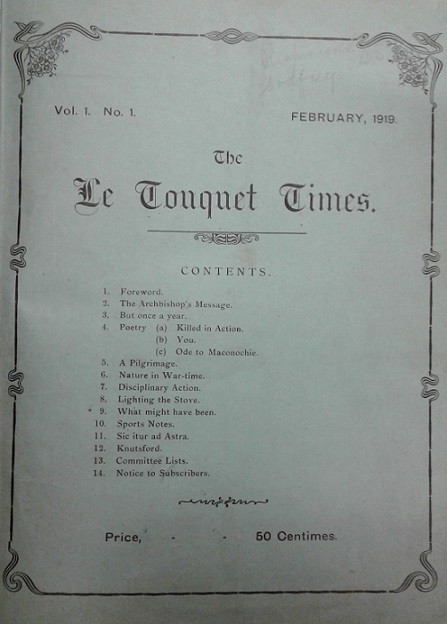

The Knutsford records are held at Cheshire Archives, including accounts, correspondence, teaching, examination, personnel, membership and other records, but the Library holds some relevant material. A single edition of its publication Le Touquet Times in the Library’s printed book collection represents its origins in France.

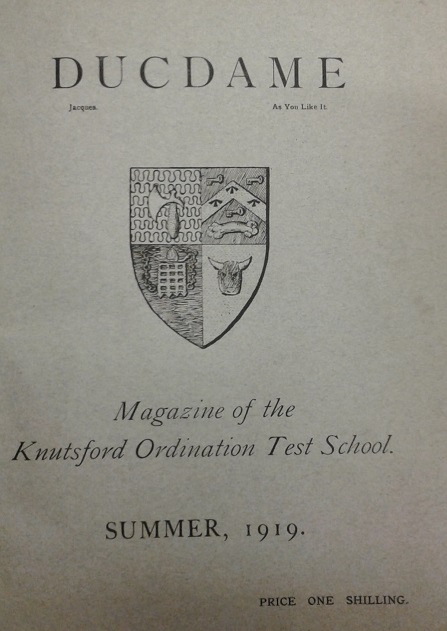

Thereafter its magazine was named Ducdame.

‘Tubby’ Clayton, founder of Toc H, was also a prime mover in this initiative. His entry in the Dictionary of National Biography records that in total some 435 men were eventually ordained. The Library holds his mark book (MS 3099) dating from 1919.