From around the 13th century, almanacs were not only produced in the most common format of medieval books – that is, the codex – but could often be found in different formats of folded books. Perhaps the best-known type is the ‘bat book’, a term coined by J. P. Gumbert in his catalogue of folded books published in 2016. He listed the 63 he was aware of, and since its publication a couple more have been identified. But why are they called bat books? To quote his catalogue (p. 19):

“when in rest they hang upside-down and all folded up, but when action is required they lift up their heads and spread their wings wide”.

A bat book features in our current exhibition – Unfolding Time: The Medieval Pocket Calendar (now in its final days of opening) – and in our video below, Lambeth Palace Library staff talk about refolding the book into its original structure for display in the exhibition.

The folding and refolding of these items raise many questions into the care of these books, which Library Conservator, Meagen Smith, speaks about in the video. But what isn’t discussed is the challenge of their curation – namely, how can we give visitors an idea of how the bat book works when it’s displayed as a still object behind glass?

Positioning

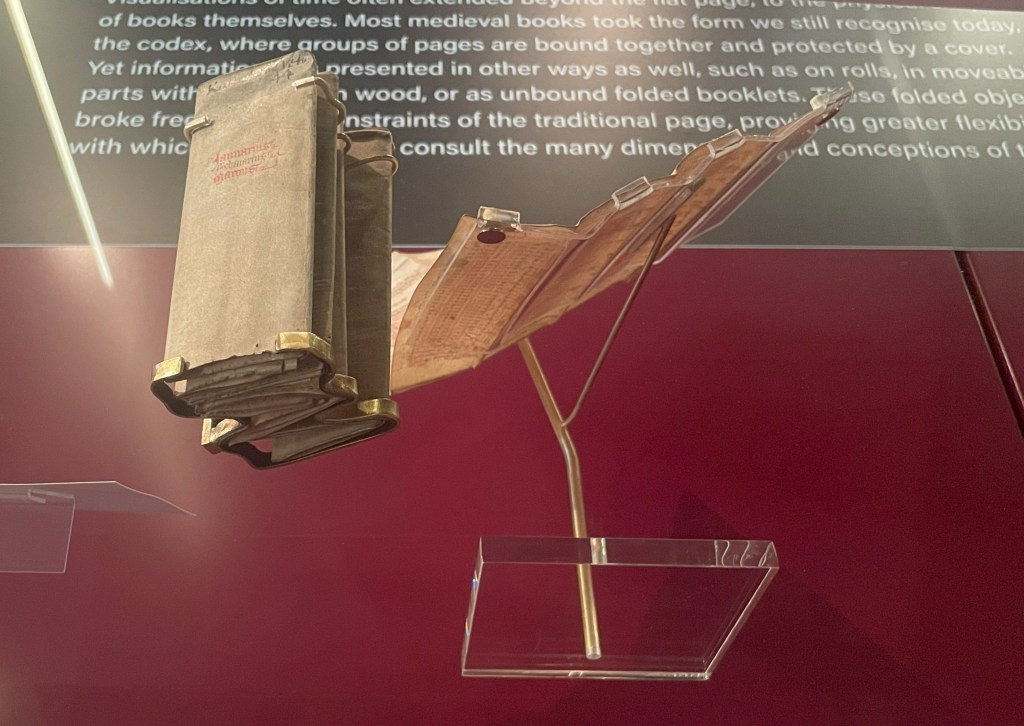

One approach was to show the bat book in two different states of (un)folding: open and closed.

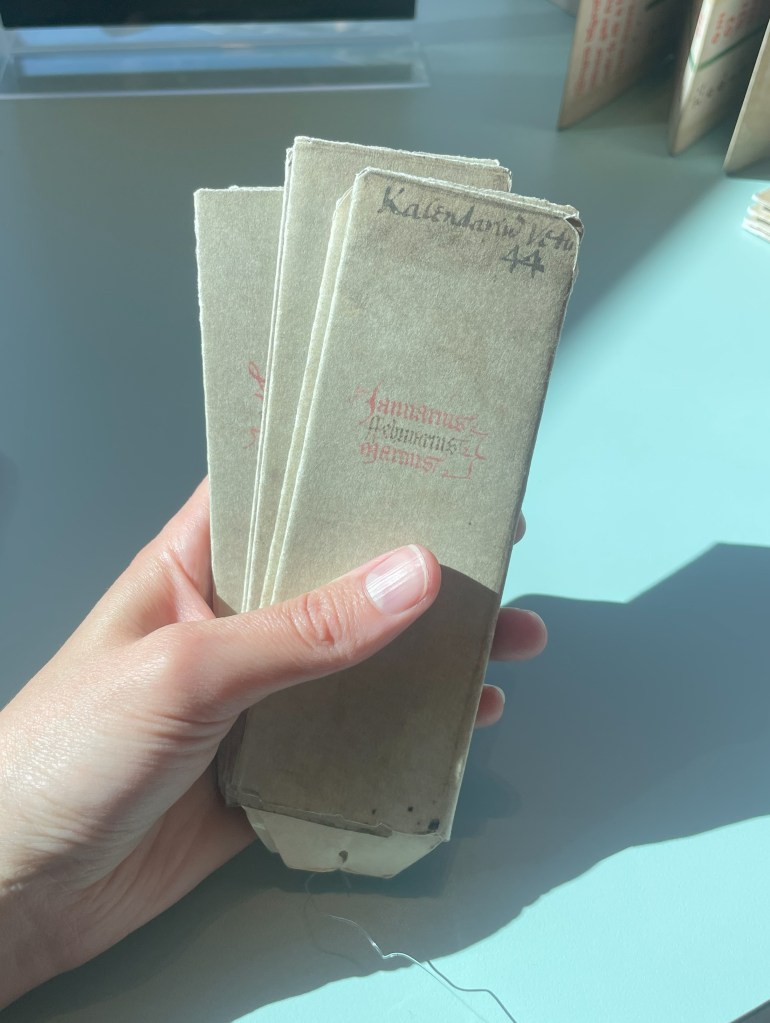

1. Closed. Above on the left we see each of the leaves closed and stacked next to one another, showing how they would have originally been positioned together when closed. On the front, we can see three months written in Latin (Januarius, Februarius, Martius), helping users flicking through the leaves to find the relevant month to unfold and consult. As the leaves have been kept flat in recent years, the parchment (thicker and more durable than paper) wants to bounce back open, and so here they are contained by a brass mount. We could have shown the leaves tightly pressed together, but we chose instead to give viewers a sense of how they begin to unfold.

2. Open. Beside this we show one leaf mid-flight, as if opened by the reader to view the calendar—in this case, for the months of November and December. Displaying them side by side also helps to emphasise the portability of the book, which opens to become eight times its folded dimensions. The mount (pictured below from below), made specifically for this leaf of the manuscript, supports it in a position that is open enough to show the inner contents whilst also communicating the shape of the folds.[i]

Facsimiles

Even with diagrams, videos, and display techniques, it remains difficult to fully grasp the structure of these books without handling them. The Lambeth bat book presents an additional challenge – the tabs with which the leaves were once bound together have been excised. To address this, we created a facsimile positioned just outside the exhibition entrance – within view of the original – which also serves as a partial reconstruction, featuring additional yellow tabs. By printing images of the bat book onto parchment paper, we aimed to convey the effect the material’s thickness has on the book’s folding and movement. The bat book recreation was a multi-step process involving members from our Archives, Operations and Collections Care teams, and we are especially grateful to Jonny Davies (Digital Officer) and Tal Wachtelborn (Project Conservator) for their contributions to the facsimile’s creation.

We are not the first to create a bat book facsimile, and we hope we won’t be the last. Jacqui Carey, for instance, has documented her own recreation of a bat book from the Wellcome Collection in a series of blog posts. More broadly, recent exhibitions have focused on books with moving parts – such as Suzanne Karr Schmidt’s Pop-up Books through the Ages and Dot Porter’s The Movement of Books – and developed resources that allow visitors to engage with these objects through manual handling in the exhibition space. In an age where digital tools play a central role in how we study and interpret manuscripts, facsimiles serve as a vital counterbalance. They remind us of the importance of tactile experience, especially for books whose structure and physical manipulation are essential to their meaning.

Sarah Griffin, Assistant Archivist and curator of Unfolding Time

Further Reading

Jacqui Carey, Somer’s ‘Kalendarium’, Part 1: folded tabs on The Book and Paper Gathering (2020)

J. P. Gumbert, Bat Books: A Catalogue of Folded Manuscripts Containing Almanacs or Other Text, Bibliologia 41. Turnhout: Brepols, 2016. (LPL: Z6602.G8)

For more on the use of bat books in the Middle Ages, see Kathryn Rudy, ‘Medieval medicine: astrological ‘bat books’ that told doctors when to treat patients’ on The Conversation (2019)

[i] The mounts for the Lambeth Palace Library objects in the exhibition were created by Zoe Harper. You can find out more about her work on her website.