Our guest contributor, Dr Sian Witherden (Rare Books and Manuscripts specialist) guides us through the Zodiac Man in a book of hours printed by Wynkyn de Worde (1526), currently on display in Unfolding Time.

What connects Aries to the head and Pisces to the feet? These questions might spring to mind when viewing the Zodiac Men on display in Unfolding Time: The Medieval Pocket Calendar, a free exhibition now open at Lambeth Palace Library. Focusing on an early sixteenth-century printed book of hours, this blog post sets out to demystify and contextualise the striking diagrammatic tradition.

Worde (London, 1526). Lambeth Palace Library, [ZZ]1526.2, sig. B1v.

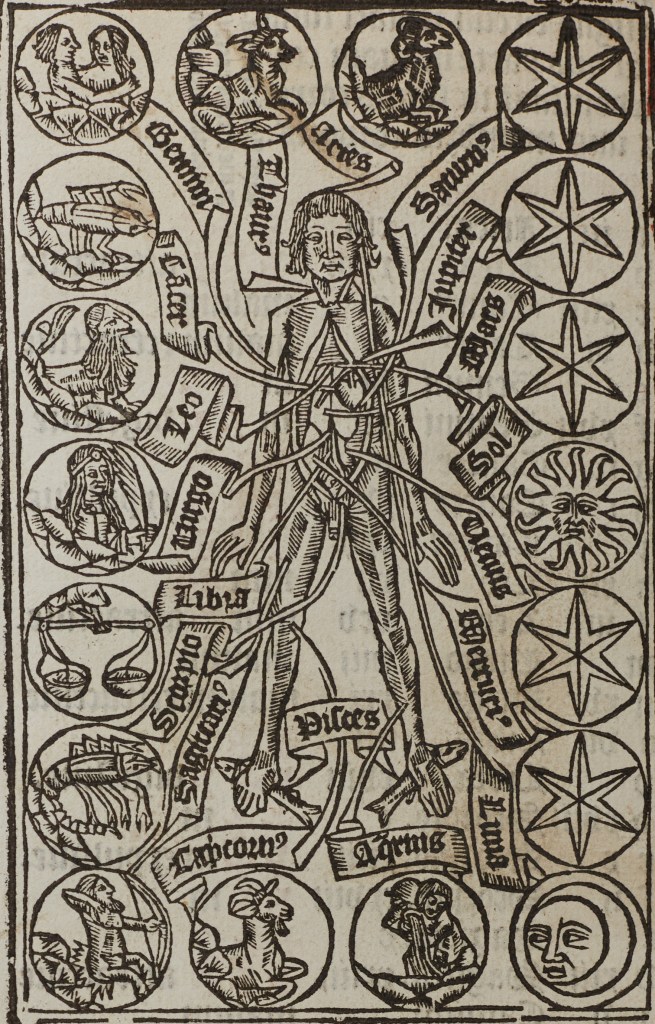

The Zodiac Man, also known as Homo signorum, expresses a core idea in medieval medicine: the moon was thought to exert a powerful influence over the human body. According to this line of thought, each part of the body was governed by one of the twelve signs of the Zodiac, and it was especially dangerous to operate or perform bloodletting in that area when the moon was in the corresponding sign. For example, if the moon is in Pisces, cutting into the feet should be avoided.

Zodiac Men diagrams summarised this aspect of lunar astrological medicine in a striking way, with the human body labelled from head to toe according to the corresponding signs. Such diagrams appeared in various contexts in medieval and early modern Europe including medical treatises, calendars, and books of hours.

Books of Hours

Known in Latin as Horae, books of hours were a type of prayer book hugely popular in Europe between the fourteenth and the mid-sixteenth centuries. Such books circulated in both manuscript and printed forms and were typically quite small and therefore portable – one book of hours exhibited in Unfolding Time (MS 3561) measures just 6 x 9 cm when closed, and fits comfortably in the palm of one’s hand. Their central text is the Hours of the Blessed Virgin (Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis), comprising devotions for the eight canonical hours of the day: Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline.

This book of hours on display in Unfolding Time was printed in 1526 by Wynkyn de Worde (d. 1534), the first printer of London’s Fleet Street. During his successful career, de Worde printed over nine hundred editions, with numerous books of hours among them. The title page for this one can be seen here:

Worde (London, 1526). Lambeth Palace Library, [ZZ]1526.2, sig. A1r.

This design emphasizes de Worde’s identity as the successor to England’s first printer, William Caxton (d. 1491). The ‘W. C.’ initials in the border and in the centre are adapted from Caxton’s distinctive printer’s device – effectively an early form of logo used to brand books for marketing and security purposes.

As is customary, this book of hours opens with a perpetual calendar identifying important days throughout the year, for example saints’ days. (The case immediately outside the Unfolding Time exhibition room offers an excellent introduction to how to read a medieval perpetual calendar). Shortly thereafter follows the Zodiac Man, which is also perpetually relevant because it is tied to the cyclical movement of the moon throughout the year.

A closer look at the Zodiac Man

Interestingly, 1526 was not the first time Wynkyn de Worde used this woodcut: it previously made appearances in books of hours printed by him in 1519 and 1523. Reusing woodcuts in this way was common in early printing, as it was highly economical.

At the heart of the diagram is a representation of an archetypal man, his torso open to reveal the inner workings of the body:

Worde (London, 1526). Lambeth Palace Library, [ZZ]1526.2, sig. B1v (detail).

Many Zodiac Men are labelled with just the twelve signs of the Zodiac, but this is a more elaborate version. Surrounding the man are eighteen circles, eleven of which provide pictorial representations of the Zodiac (the twelfth Zodiac sign, Pisces, is illustrated via the two fish underneath the man’s feet). The remaining circles are for the so-called ‘seven planets’, i.e. Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, and the Moon. Individually, these were also associated with specific body parts; for example, Saturn governed the spleen.

The twelve Zodiac signs and seven planets are labelled using small banners known as ‘banderoles’, each connected up to the relevant body part. The text beyond the border of the diagram, which can be seen on the full-page image at the beginning of this blog post, provides another summative explanation of the equivalences.

Accompanying the Zodiac Man

The facing page (shown below) provides more detailed information about the associations between body parts and the Zodiac. To help the reader navigate this text, each Zodiac sign is introduced by a paraph, also known as a pilcrow – you may have seen a modern version of it when using word processing software ( ¶ ).

The book also contains a table (shown below), which works well in tandem with the Zodiac Man. By carefully working through this table, readers could calculate the place of the moon in the Zodiac for any day in any year. This information would be helpful in determining whether it was a good or bad time to perform certain procedures, such as bloodletting. For comparison, an English manuscript from 1583 contains detailed instructions for how to read a very similar table (Osler Library of the History of Medicine B.O. 7601, pp. 38-43). A transcription of the relevant section can be found here.

Worde (London, 1526). Lambeth Palace Library, [ZZ]1526.2, sig. B1r.

Who would have read this kind of book, and how might they have used the Zodiac Man and associated information? Printed books of hours like this one would have been cheaper than their lavishly illuminated manuscript counterparts, and more generally de Worde’s ‘main contribution to the printed book trade was his prolific production of affordable, attractive books, which were often illustrated, always in the most economical way’ (Driver 1996, p. 349). Unfortunately, there are few clues as to the early provenance of this specific copy. More generally, laypeople encountering a book like this one might have consulted the Zodiac Man and accompanying texts to help them make decisions about, for example, the best times to seek out the services of a bloodletter. The Lambeth Palace Library copy of this edition is one of just two known to survive, and it sheds fascinating light on an iconographic tradition popular in medieval and early modern culture.

Online Resources

A full digitization of Lambeth Palace Library, [ZZ]1526.2 is available via ProQuest (https://www.proquest.com/eebo/docview/2248514247).

For further details on the edition, see ESTCS124993 (cf. Print & Probability stopgap version) (https://estc.printprobability.org/), and USTC 501958 https://www.ustc.ac.uk/editions/501958). See also at Pollard and Redgrave, Short Title Catalogue, no. 15948.

Phillips, Laura, Medical Astrology: Science, Art, and Influence in early-modern Europe, online exhibition. The Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library and Medical Historical Library at Yale University, July 2021. Accessible here. https://onlineexhibits.library.yale.edu/s/medicalastrology

Yearl, Mary, ‘Balancing information and expertise: vernacular guidance on bloodletting in early modern calendars and almanacs’, Folger Shakespeare Library blog, posted 9 February 2021, accessible here https://www.folger.edu/blogs/collation/balancing-information-and-expertise-vernacular-guidance-on-bloodletting-in-early-modern-calendars-and-almanacs/

A selection of further reading

Driver, Martha W., ‘The Illustrated de Worde: An Overview’, Studies in Iconography 17 (1996): 349-403.

Duffy, Eamon, Marking the Hours: English People and their Prayers, 1240-1570 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006). LPL: RD3363.D8

Hodnett, Edward, English Woodcuts 1480-1535 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973). [For this Zodiac Man, see no. 898c]. LPL: Z1008.B5 [R]

Jensen, Phebe, Astrology, Almanacs, and the Early Modern English Calendar (London: Routledge, 2020).

Moran, James, Wynkyn de Worde: Father of Fleet Street, 3rd rev edn (New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2003). LPL: Z232.W6M6

Sand, Alexa, ‘Moving Pictures: The Art and Craft of Dying Well in the Woodcuts of Wynkyn de Worde’, in Vernacular Books and Their Readers in the Early Age of Print (c. 1450–1600), ed. by Anna Dlabačová, Andrea van Leerdam, and John J. Thompson (Leiden: Brill, 2023), pp. 198-228. [For de Worde’s reuse of woodcuts]

Witherden, Sian, ‘Balancing Form, Function, and Aesthetic: A Study of Ruling Patterns for Zodiac Men in Astro-Medical Manuscripts of Late Medieval England’, Journal of the Early Book Society 20 (2017): 79-109.